Bilingual Language Development - The Facts

Bilingual language development occurs when a young child is learning to speak two languages. This can mean 2 languages in one home, or one language at home and another language in another setting such as school or their parent’s work.

If a child is learning more than two languages, it would be considered multilingual language development.

The 2019 Census showed that about 23% of school age children in the US spoke a language other than English, which means that bilingualism and multilingualism is very common amongst children.

There are two main categories of bilingual language development or language learning:

Simultaneous: when a child is learning two languages at the same time, often from infancy. For example a family that speaks both English and Arabic at home daily.

Sequential: when a child learns one language, then later learns a second language. For example a child learns English at home, and then enrolls in a Spanish-immersion kindergarten class.

Common questions about simultaneous bilingual language development.

For young children, many families have concerns or questions about bilingualism. Families are thinking about simultaneous bilingual learning in situations like one of these:

My partner and I speak English at home, but Grandma watches Marta during the day and speaks only French to her

We speak “Spanglish” --a mix of English and Spanish at home

Our daycare providers speak English, but we speak Vietnamese at home.

No matter the circumstance, every parent is wondering the same thing: Is learning more than one language keeping my child from talking?

Being bilingual does not keep children from talking!

Old beliefs were that children needed to solidify learning one language before introducing them to another language--to not confuse them. But recent research has debunked this myth: kid’s brains are capable from a young age to learn multiple languages at the same time!

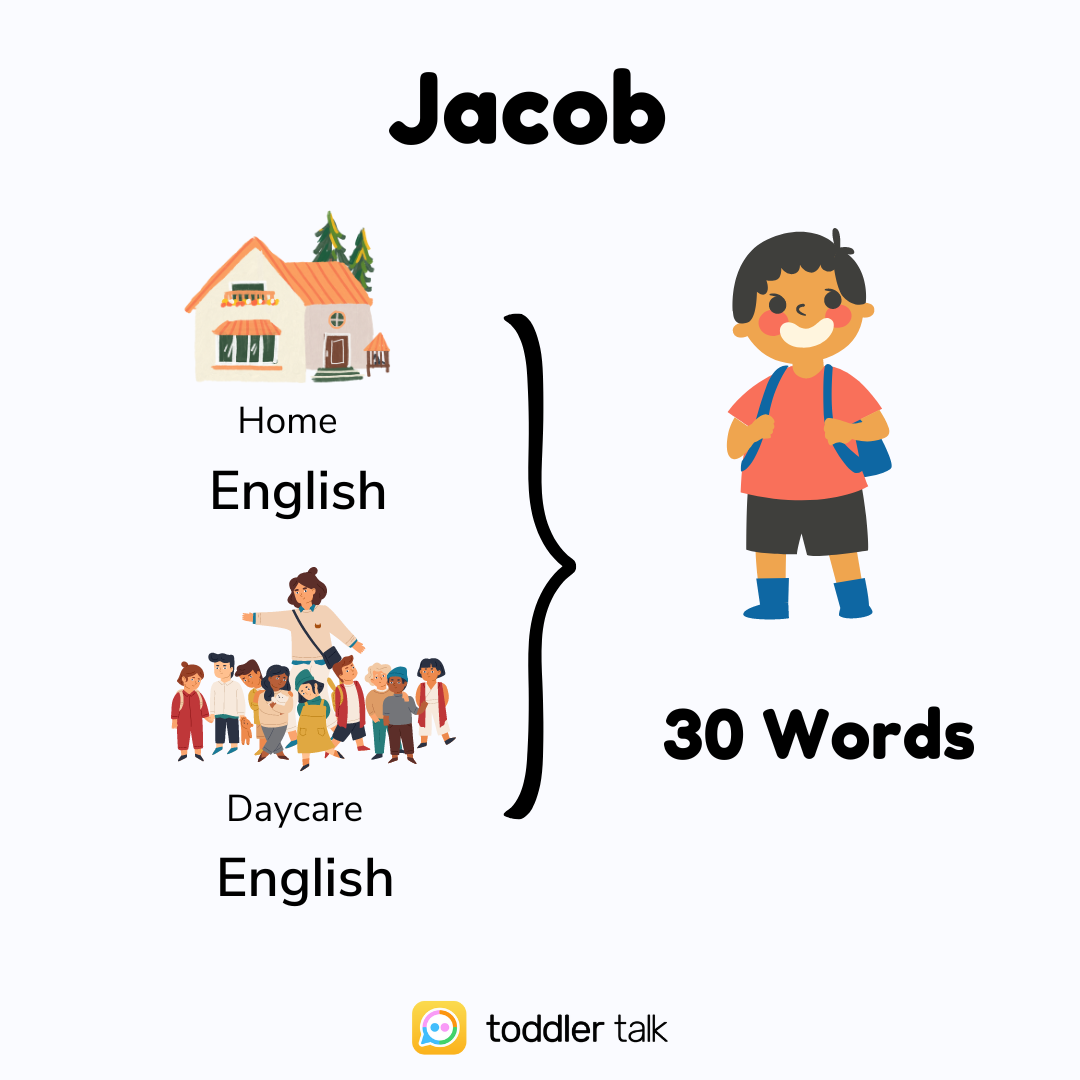

Here’s two scenarios of 18 month old toddlers:

Jacob: only exposed to English, both at home and at daycare. Says 30 words, all in English

Marta: exposed to English at home and French with Grandma during the day. Says 18 words in English, and 15 words in French, for a total of 33 words.

Both children are on track with their single-word development. But their makeup looks different. If you only counted Marta’s English vocabulary, she could look behind. But it is crucial that with bilingual children, we are looking at their total communication profile: how much do they say total, not just in one language or the other.

So, what we expect from simultaneous bilingual children is this:

If a child is learning language typically, they will learn it at an approximately equal rate of learning as compared to monolingual peers, when you look at their total communication profile.

If a child is struggling to learn language, they will struggle in both languages.

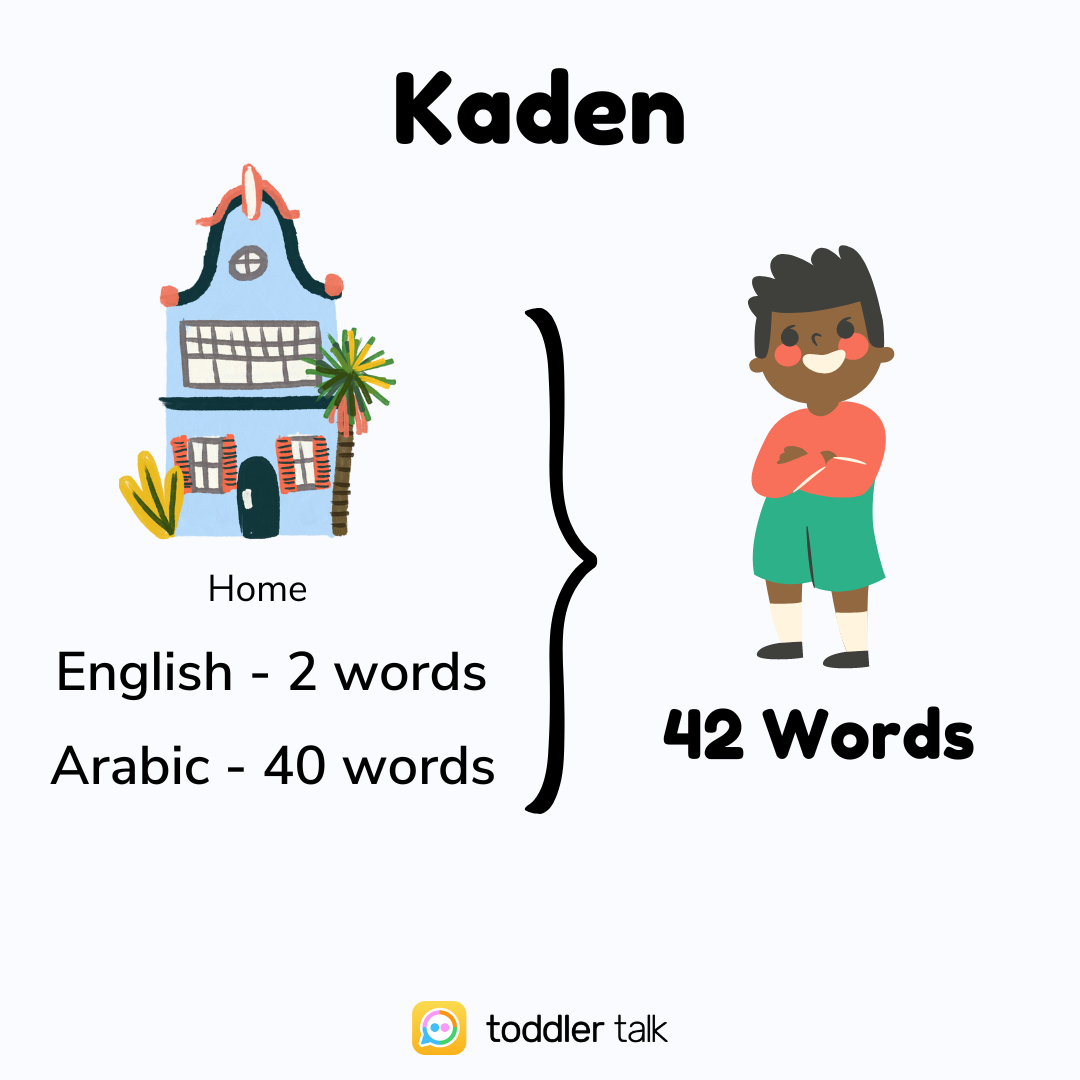

Here’s two more scenarios of two more 18 month olds:

Kaden: exposed to both English and Arabic at home. He says 2 words in English and 40 words in Arabic, for a total of 42 words.

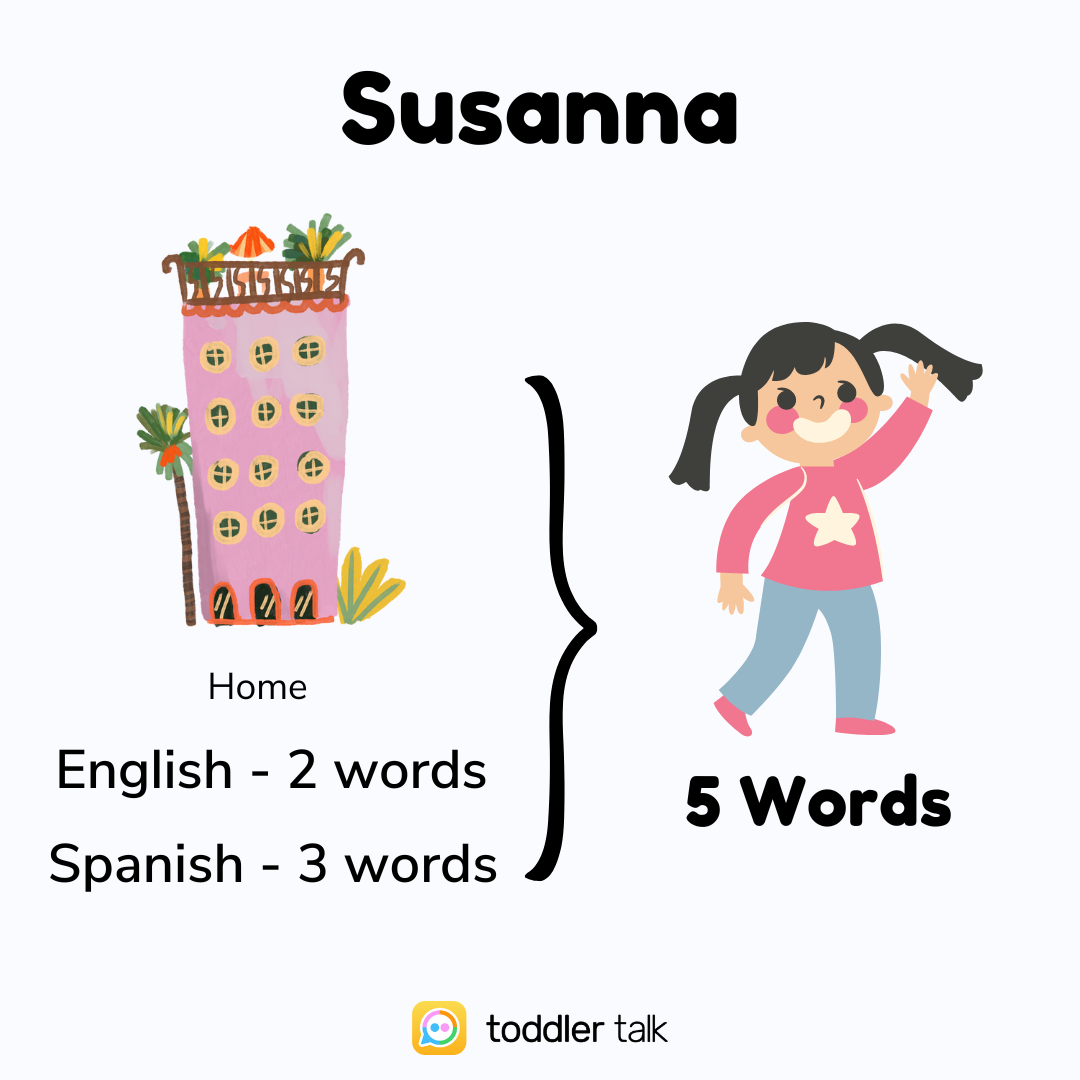

Susanna: exposed to both English and Spanish at home. She says 2 words in English and 3 words in Spanish, for a total of 5 words.

See how Marta, Susanna, and Kaden all have simultaneous bilingual exposure, but have very different number of words. Marta has a close to equal number of words in her two languages; Kaden has much more of one language than the other– neither of these examples indicate a language delay and both demonstrate good language learning.

Of all the scenarios listed, the only one that would concern me is Susanna. She only says 5 words total, indicating a concern for how she is learning language in general, not her exposure to two languages.

If your child is not talking at an expected rate, that may be a concern, regardless of their monolingual, bilingual, or even multilingual exposure.

Let’s talk about the evidence in favor of bilingual language development

There are TONS of research studies looking at many different language combinations, and across the board researchers have found that bilingual or multilingual language exposure and language development does NOT cause language delays or disorders, or confuse children. In fact, there are some benefits to being bilingual.

Here are a few of those research studies and what they found in case you wanted to take a look at them.

Growing up bilingual does not cause language learning deficits or language disorders→ Fibla, et al. 2022 & Paradis, Genesee, & Crago, 2011

Bilingual children know about the same number of words as monolingual children if you add together the words they know in each language (known as conceptual vocabulary) → Marchman, Fernald, & Hurtado, 2010) & (Pearson & Fernández, 1994).

Bilingual children are equally as likely as monolingual children to have a language delay or a language disorder → Byers-Heinlein & Lew-Williams, 2013

Bilingual children develop language skills without confusion or delay → Werker & Byers-Heinlein, 2008

Bilingual children may have advantages in social understanding, like being able to take other people’s perspectives more easily → Yow & Markman, 2011

Research has shown that infants and toddlers have cognitive advantages over children learning just 1 language → Kovács & Mehler 2009 & Poulin-Dubois, Blaye, Coutya,& Bialystok 2011

I’m wondering if my child has a speech or language delay. How do I get them tested?

A speech-language pathologist is the person who diagnoses speech and language delays.

When scheduling a speech and language evaluation for your child who is learning to speak more than one language you can always ask to see if there is a bilingual speech therapist available. You may be surprised, especially at larger institutions like children’s hospitals, that there are speech therapists who speak many different languages.

And if the speech therapist doesn’t speak your language you can always ask for an interpreter!

Related: How to find a pediatric speech therapist near me & What to expect at a speech and language evaluation

Okay, now you’re probably wondering, “What can I do at home to support bilingual speech and language development?”

High quality & high quantity language input is key!

What does that mean?

Well, high quality is going to look different for everyone. High quality language input means using the language(s) you are most proficient in. The best thing you can do for your child is give them high quality and grammatical language input throughout the day, in whatever language(s) you speak naturally.

High quantity means that children need to hear you talk a lot in order to learn to talk themselves. Repetition is key!

Let’s talk about a few more important topics:

One Parent - One Language - Infants can perceptually separate the languages their parents are speaking from birth. You do NOT need to use a “one parent- one language” strategy because infants can use several different cues, including the patterns of sounds and rhythms of the languages, to learn separate language systems! How cool! Here’s what the researchers say, “One parent one language is neither necessary nor sufficient for bilingual language development” Byers-Heinlein, K., & Lew-Williams, C. (2013).

Code Switching - Code-switching is a rule governed way that adults transition between two languages when talking. If you code switch, you should keep doing it. Code switching won’t confuse children and they can still learn to talk in both languages you use. If you are teaching or modeling specific grammatical skills in one language, it can be helpful to keep one language per sentence to give the complete model in one language.

Speech Therapy For Bilingual Families - I know I mentioned already that you can ask to see if there is a bilingual speech therapist available near you. If there is not, you can, and should, take the strategies you learn in speech therapy and use them at home in all the languages you speak. Even if your speech therapist only speaks English, they can still help you brainstorm how you’re going to practice in other languages.

Here are other questions parents are asking about bilingualism:

-

Bilingualism does not cause a language delay or language deficits. But it does mean that there may be some differences when compared to monolingual peers. For example, a child who is bilingual may have less words in a single language than a monolingual peer, but they will have the same number of total words if you add together all the words they say in both their languages.

-

Bilingual children start talking at the same time as monolingual children. They will say their first words between 10-14 months.

-

Absolutely! Children are born with the ability to hear and learn more than one language.

Written By: Stephanie Keffer, MS CCC-SLP & Melissa Sartori, MS CCC-SLP

References List:

De Houwer, A. (2007). Parental language input patterns and children's bilingual use. Applied psycholinguistics, 28(3), 411-424.

© 2020-2025. Stephanie Keffer Hatleli, MS CCC-SLP. All Rights Reserved.

The content offered on ToddlerTalk.com is for informational purposes only. Toddler Talk is not engaged in rendering professional advice, whether medical or otherwise, to individual users or their children or families. No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor, speech language pathologist, or other health professional. By accessing the content on ToddlerTalk.com, you acknowledge and agree that you are accepting the responsibility for your child’s health and well-being. In return for providing you with information related to home speech and language practice, you waive any claims that you or your child may have as a result of utilizing the content on ToddlerTalk.com.